The Hidden Truth Behind the Only Survivor at Cielo Drive

A reconstruction of William Garretson’s testimony, polygraph, and the erased version Hollywood relied on.

He always said he heard nothing.

Five people were butchered a few metres away, and the nineteen-year-old in the guest house insisted the night passed in silence.

But Garretson is more than a footnote. On my channel, he consistently draws the highest engagement — because he sits at the fault-line between myth and memory. His story is the place where the official narrative cracks.

He looks haunted in those early photographs — microphones shoved into his face, flashbulbs exploding — like a boy who already understood the cost of saying the wrong thing.

The rediscovered press conference from 16 August 1969 — the moment that sent me back into the case file and led to this summary.

The Forgotten Witness

This article summarises the key findings from three longer investigations I’ve already done in live streams, each going line-by-line through the primary documents:

This piece is the case-file overview — the condensed dossier.

William Eston Garretson was the caretaker at 10050 Cielo Drive in August 1969. Hollywood remembers him as an afterthought: a timid Ohio kid paid thirty-five dollars a week to mind Rudy Altobelli’s dogs.

But every institution he encountered — LAPD, the DA’s office, the press, and Hollywood itself — had a stake in what he said, and what was erased.

Institutional betrayal isn’t always loud.

Sometimes it’s the quiet removal of a witness whose presence complicates the story the city wants to tell.

What the Documents Actually Show

Across the three primary sources — courtroom testimony, polygraph interrogation, and forensic tests — Garretson repeats one claim with unnatural consistency:

Court Testimony (1970)

He leaves at 8 p.m., returns around ten, and leaves the back door open all night.

Steven Parent visits briefly, trying to sell a clock radio, makes a phone call and leaves.

He says he sat up all night writing letters and listening to records at volume 4, The Doors and Mama Cass. He swears he heard no screams, no gunshots, no movement — not even footsteps on gravel.

Whole article about his court testimony here:

Polygraph (1969)

The same story, with one crucial new detail:

the door handle turning, the dog barking, and the sudden fear that freezes him.

He passes the major questions:

Didn’t harm Parent

Didn’t see the murders

Didn’t know the killers

Admits LSD, weed, and speed

Mentions strange incidents earlier that year

Appears frightened, uncertain, evasive

Shows memory gaps

He also tells the examiner something that rarely appears in mainstream accounts: earlier in the year, he saw a nude woman being filmed at the pool by Abigail Folger and Voytek Frykowski. This detail, buried in the polygraph file, becomes significant when we look at the fingerprint on the freshly cleaned poolside door and Bugliosi’s warning about the supposed “swim meet.”

The “Swim Meet” Problem

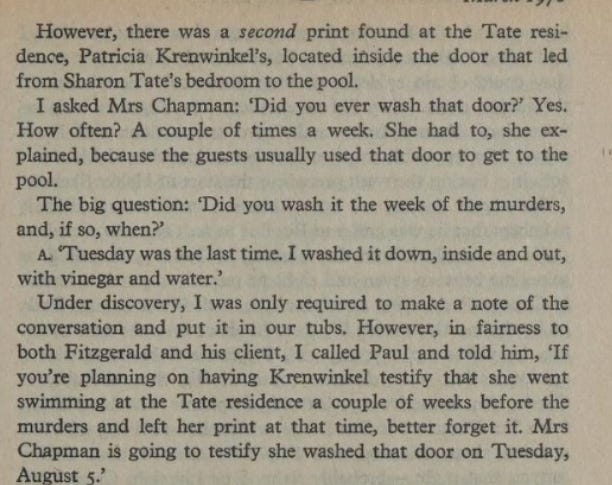

Then we hit the detail Bugliosi accidentally exposes in Helter Skelter:

a fingerprint on a freshly cleaned door by the pool — the same door that Garretson once saw a nude woman being filmed through by Frykowski and Folger. Bugliosi warns Krenwinkel’s lawyer not to mention she’d been at a “swim meet” earlier in the year, because the maid had cleaned that door shortly before the print appeared.

This is the root of a long-running rumour: that Krenwinkel did come to the guest house that night, saw Garretson awake, and told him to stay quiet — possibly because she recognised him from something that had happened at the house months earlier. It’s speculative, but it’s been part of the case for decades because it explains his behaviour: the paralysis, the fear, the refusal to open the door.

Warren Beatty’s biography, along with other sources, mentions more than one Manson girl using the pool at Cielo Drive that summer. If Garretson encountered any of them at these informal gatherings, it would destroy the prosecution’s favourite myth — that the killers had no link to the victims.

And it gives shape to a fear Garretson could never quite articulate.

Forensic Sound Tests

LAPD’s sound test was done in daylight, with shots fired into sandbags.

Not the real conditions.

Not the real acoustics.

Not the real distance.

The test doesn’t prove what he could hear.

It proves the institution needed him to have heard nothing.

Hidden in Plain Sight, Memory & the Erased Witness

Garretson’s evasiveness fuelled darker rumours around the guest house itself.

Some revolve around Hollywood agent Rudi Altobelli and the allegation that he sometimes placed young men there for reasons never fully clarified. One rumour — entirely unproven — is that Garretson was installed as a rent boy. Nothing in the case file supports it.

Another whisper places Cary Grant at the guest house. Again, nothing concrete has ever surfaced.

These stories say more about the era — and the way queer Hollywood operated in the shadows — than they do about Garretson.

For deeper context, I’ve written separate dossiers: Rudi Altobelli’s Hollywood shadows →

The Cary Grant guest house rumour →

Still, these rumours explain why he may have been evasive about who came and went — and why certain details around the property have a murky quality. It’s the pattern of a witness caught between Hollywood secrecy and a police investigation looking for simple answers.

Garretson becomes the archetype of a witness hidden in plain sight.

Every system around him benefited from reducing him to a non-entity.

A harmless boy who heard nothing.

No complications.

No inconvenient timeline.

But trauma reshapes memory.

A teenager dragged to three bodies, interrogated without sleep, and publicly accused often ends up with memories that are not factual, but assembled.

By 1999, his new “memories” resemble something half-remembered, half-absorbed — narrative debris built from decades of speculation.

THE 1999 DOCUMENTARY CLIP

Three decades later, he remembers something else entirely:

a scream,

a girl chasing another girl,

and a voice saying: “Stop, stop, I’m already dead.”

Even he admits it didn’t make sense.

Is it trauma, rumour, suggestion, or confabulation?

We don’t know.

That ambiguity is the point.

By 1999, he had spent thirty years marinating in rumours.

It’s entirely possible that his later “memories” weren’t memories at all — just narrative debris from decades of being discussed rather than believed.

(Video set to start where Garretson speaks, you only need to watch about 1 minute to see Garretson’s update).

In the documentary, Garretson gives a very different version.

By 1999, Garretson had lived with thirty years of rumours about what he supposedly heard or saw.

That kind of repeated exposure can distort memory — especially in someone who was terrified, exhausted, and dragged across a crime scene at nineteen.

Producers in the 1990s often prompted interviewees to make their answers more dramatic, and you can hear that in lines like ‘Stop, I’m already dead.’ It sounds theatrical, not like something he genuinely remembered at the time.

What he says in this later clip is vague, dreamlike, and doesn’t match the real sequence of events. It’s much more consistent with confabulation — the brain filling in gaps — than with a hidden eyewitness account.

So rather than revealing a new truth, his 1999 version is probably a mixture of fear, repetition, and suggestion. So when we watch his original press conference, we have to ask: what did he sound like before the rumour mill, before the pressure, before the confabulation?

The Quiet Question

When you study all the documents and interviews side by side, a pattern emerges:

not deception,

not complicity,

but erasure.

The erased woman filmed at the pool.

The erased prints on a freshly cleaned door.

The erased behaviour of the dogs.

The erased possibility that he might have heard something, even if he couldn’t process it.

And the question that underpins all my streams:

Who gets to tell the truth about Cielo Drive — and who gets written out of its mythology?

Garretson matters now because he shows what happens when a witness is too ordinary to fit the mythology. He wasn’t a celebrity, a victim with cultural weight, or a villain prosecutors could use. He was the boy in the guest house — the one nobody wanted, and the one nobody listened to.

He died in 2016.

No memoir.

No definitive record.

Just fragments in case files and a few minutes of frightened press-conference footage.

Maybe he heard nothing.

Maybe he heard everything.

Or maybe the truth is simpler:

Nobody wanted his version.

It wasn’t clean.

It wasn’t cinematic.

It wasn’t useful.

The myths around Cielo Drive were far more profitable than the witness in the guest house — the one whose silence made everyone else’s story easier.

So the quiet question remains:

Do we believe the first version he gave — or the one he could only tell after thirty years of being erased?

📚 Sources:

• Court testimony transcripts

• Polygraph examination (1969)

• LAPD sound test notes

• THS – The Last Days of Sharon Tate (1999)